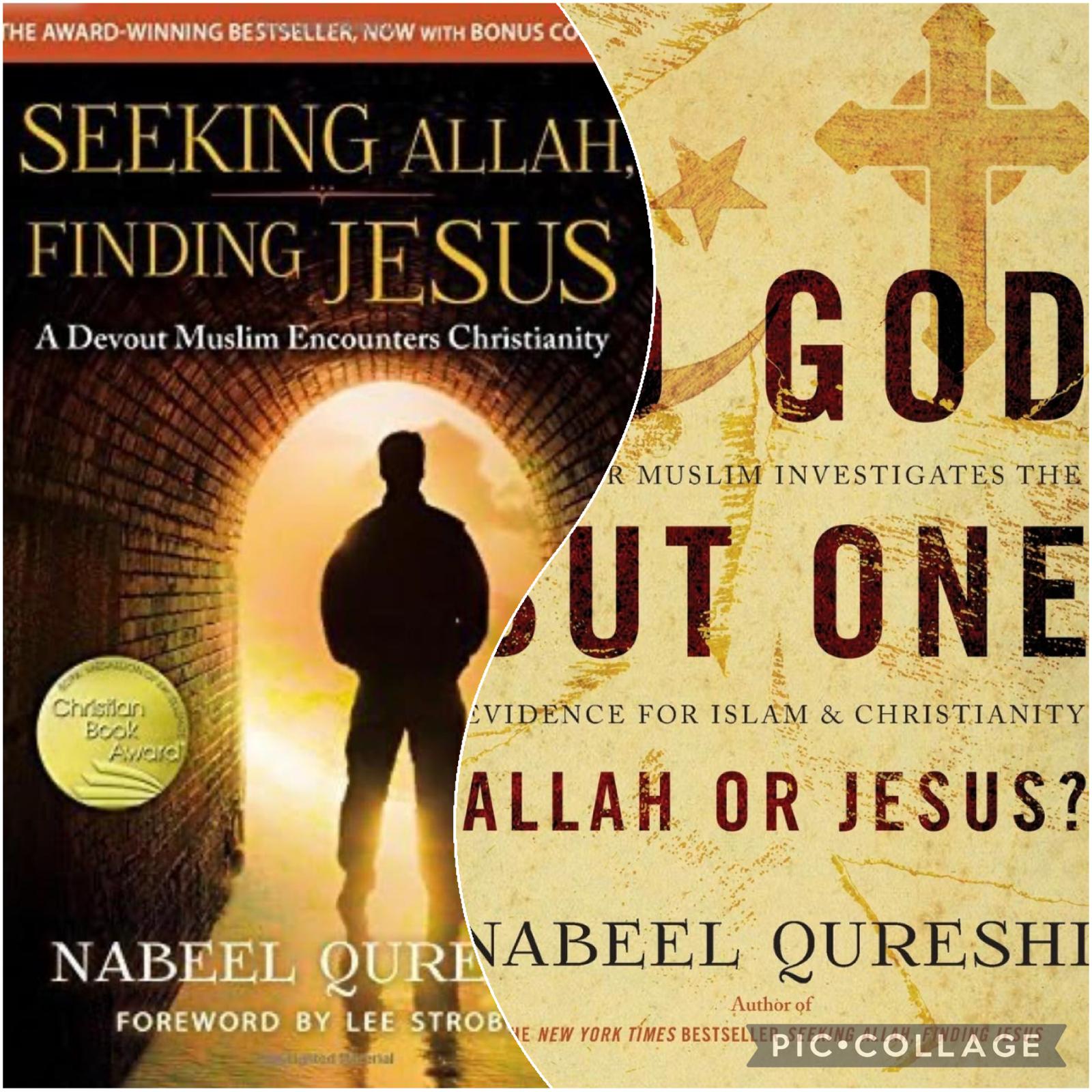

Few books have been as practically helpful to me as Nabeel Qureshi’s ‘Seeking Allah, Finding Jesus’ and its sequel, ‘No God But One: Allah or Jesus.’ As a Muslim, Nabeel wrestled with the Christian doctrine of the Trinity—having been taught that the Trinity is a thinly veiled polytheism. Consequently, he struggled with the notion of Christ’s divinity, and questioned the Christian message of salvation through Jesus’ death and resurrection.

This review summarises the biblical responses to these questions, which helped Qureshi resolve his misunderstanding of the Christian position and expose the misconceptions he had held all his life. A comprehensive review of how Nabeel came to address each issue would require an extensive article, which might deter many readers. Therefore, this piece will specifically focus on the doctrine of the Trinity. The insights shared here are primarily drawn from Qureshi’s books; augmented with additional scriptural references and commentary from other readings to underscore the points made.

Tawhid and the Trinity

The concept of Tawhid, also known as Tauheed, is a core doctrine of Islam that emphasises Allah’s absolute unity and self-reliance. Essentially, Tawhid asserts the oneness of God. This teaching highlights that the essence of God—what makes Him divine—is His singularity: He is independent, unique, sovereign, distinct, and wholly unified. According to Tawhid, there can be no division within God whatsoever.

Nabeel Qureshi describes his youthful endeavours to challenge this concept when conversing with Christians about the Trinity. He recounts,

“Whenever I had a discussion about the Trinity with a Christian, my first question was, ‘Is the Trinity important to you?’ Upon receiving an affirmative reply, I would probe further, ‘How important?’ anticipating the response that it would be heretical to deny the Trinity. The third question would complete the setup: ‘So, what is the Trinity?’ The typical answer I got was that God is ‘three in one.’ Then came the coup de grâce: ‘And what does that mean?’ Typically, this resulted in blank stares. Occasionally, someone would attempt analogies involving eggs or water, but no one could clearly articulate what the doctrine of the Trinity actually meant. How could God be three in one, and how is that not a contradiction?“

Regrettably, Nabeel noted that none of the Christians he engaged with before meeting David Wood—who played a significant role in his conversion to Christianity—could satisfactorily explain or articulate the meaning of the Trinity.

Expounding the Christian Doctrine of the Trinity

As Nabeel intimates, many Muslims perceive the Christian concept of the Trinity with suspicion, often equating it to polytheism due to a misunderstanding of Christian monotheism. This confusion is not uncommon, as both Jewish and Islamic traditions emphasise the oneness of God, often referred to as a monad, which seems at odds with Christian doctrine. So, how does Christian theology reconcile this with the biblical affirmation of God’s oneness?

One of the most pivotal biblical texts in this discussion is the Shema, a traditional Jewish prayer from Deuteronomy 6:4, which declares,

“Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one.”

This verse is also reflected in Romans 3:30. The question then arises: How do Christians interpret this declaration of God’s oneness within the framework of the Trinity?

In Christian theology, the distinction between “being” and “person” helps clarify this concept. “Being” refers to the essence or quality that makes you what you are, whereas “person” is the quality that makes you who you are. For example, we are humans. That is what we are. That is why we are called human beings. But what we are is not the same as who we are. If someone asks me, “Who are you?” I should not respond by saying, “A human!” That answers the question of what I am, not who I am. Who I am is Ebenn; that is my person. What I am is a human; that is my being. Being and person are separate.

Unlike humans, who each have one personhood, God is one Being manifested in three distinct Persons: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. This understanding does not imply polytheism; rather, it posits a single divine essence shared equally but distinctively among three persons. Such a concept challenges human comprehension, which is often why analogies fall short. To say God must fit within our limited human understanding of personhood is to attempt to create God in our image rather than accepting His self-revelation.

Christian theology maintains strict monotheism while embracing the mystery and complexity of God’s revealed nature by emphasising that God’s triune nature does not compromise His oneness. Thus, when Christians recite the Shema, they affirm God’s oneness but understand it through the lens of a triune identity.

How is the Trinity Not a Contradiction?

One of the foundational principles in logic is the law of non-contradiction, which states that something cannot be both true and not true at the same time when dealing with the same context or relationship1. For instance, I have a fourteen-year-old son named Ekow. It’s impossible for me to be both a father to Ekow and simultaneously his son. This is because one cannot hold the roles of both parent and child in the same relationship at the same time.

However, consider a different scenario: I am a father to Ekow and also a son to Edward Foster-Nyarko. These are distinct relationships where no contradiction exists because the roles are not assumed under the same circumstances or relationships.

When we describe God as “three in one,” we don’t mean three and one in the same relationship. That would be a contravention of the law of non-contradiction. However, we mean that God is one in His being while existing as three persons—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Each person of the Trinity shares the same divine nature but remains distinctly personal, allowing for relational distinction without contradiction. To be sure, that is paradoxical or hard for our puny minds to comprehend, but it is by no means contradictory.

Understanding Composite Oneness in Hebrew Verbiage

The word “one” in the Shema is derived from the Hebrew root echad (אחד), often understood to signify a composite or compound unity. This concept is illustrated throughout the Hebrew Scriptures where “echad” encompasses a union of multiple elements to form a unified whole.

For example:

- In Genesis 1:5, the text describes how evening and morning together constitute “one day”.

- Genesis 1:9 mentions the gathering of waters under the heavens into “one”.

- In Genesis 2:24, a husband and wife are said to become “one flesh”.

- Genesis 11:6 depicts the people of Shinar becoming “one”.

- In Genesis 34:16 and 22, Jacob’s sons propose to the men of Shechem: when Jacob’s sons proposed to the men of Shechem to be circumcised, so they dwell with them as “one” people.

Further illustrations include:

- Numbers 13:23, where a cluster of grapes is described as “one” cluster.

- Ezekiel 37:17, where the prophet is commanded to join two sticks, so they become “one” symbolising the reunification of Judah and Israel.

These instances highlight the use of echad to denote a complex unity, where multiple components form a cohesive whole.

Although the use of echad in Hebrew verbiage is not restricted to composite unity (see Exodus 11:1, 17:12, and 25:19), it certainly allows for composite unity. This understanding of “one” as a composite unity thus provides a framework for theological concepts like the Trinity, where God is described as one in essence but comprising three distinct persons.

Verses that teach the Trinity in the Old Testament

Nabeel Qureshi had been taught that the concept of the Trinity was a Christian invention to justify the worship of Jesus, purportedly absent in the Old Testament. However, an examination of the Hebrew scriptures suggests that the roots of Trinitarian thought can indeed be found in the Old Testament, not just the New.

The Trinity at Creation

Genesis 1:1 states: “In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth.” The Hebrew word translated as “God” here is Elohim, which is grammatically plural. If taken literally, it might be translated as “Gods.” However, the accompanying verb (“created”) is singular, indicating a singular subject. So, right at the very beginning of the Bible, we see that God is in some sense plural but in some sense singular. This fits perfectly with what we’ve said earlier: God is plural in terms of His persons but singular in terms of His Being.

It is no wonder, therefore, that in verse 26 of Genesis 1, God refers to Himself in the plural: “Let us make man in our image”. We could take this to mean a plural of majesty – the way a king might use “we” to refer to himself. Allah does this in the Quran (use “we”). While such usage is common in some languages (including Arabic), it is helpful to note that nowhere does Biblical Hebrew employ this plural of majesty, so it is highly improbable that it would do so here only. The more likely explanation is that God is pointing out that He is, in some sense, plural.

In support of this, we read in Genesis 1:2 that “And the Spirit of God was hovering over the face of the waters.” John 1:1 further alludes to the fact that Jesus was the Word of God, who existed with God from the very beginning and through whom everything was created. In John 1:14, John explains that the Word is none other than Jesus, the second person of the Trinity. Thus, all three persons of the Trinity existed at creation, hence the use of “we” to refer to God’s creative action.

Two Persons of God at Sodom and Gomorrah

In Genesis 19:24, when God destroyed Sodom and Gomorrah, we read this:

“Then the Lord rained on Sodom and Gomorrah sulfur and fire from the Lord out of heaven.”

In this verse, God appears to be both on earth and in heaven, the person on earth raining down sulfur from the person in heaven!

Psalm 110:1 is another place where we see two distinct persons being referred to as God (Lord) to David:

“The Lord says to my Lord: “Sit at my right hand, until I make your enemies your footstool.”

Jesus clarifies this verse in Matthew 22:41-46, where he appropriated the verse above to Himself. This is further corroborated by the writer to the Hebrews (Hebrews 1:8).

The Redeemer as God in Three Persons

One of the most beautiful expressions of the Trinity in the Old Testament is found in Isaiah 48:12-16, where we read of all three persons of the Trinity:

““Listen to me, O Jacob, and Israel, whom I called! I am he; I am the first, and I am the last. My hand laid the foundation of the earth, and my right hand spread out the heavens; when I call to them, they stand forth together. Draw near to me, hear this: from the beginning I have not spoken in secret, from the time it came to be I have been there.” And now the Lord God has sent me, and his Spirit.”

Notice how the one speaking, who describes Himself as the first and last, in other words, “Eternal”, which can only be God, says He was sent by the Lord God, along with His Spirit. Surely, anyone authoritative enough to send the Eternal God and His Spirit must be equal to or greater than God. To erase any doubt that this is God, the very next verse says the one speaking is “the LORD”, “Redeemer”, and “the Holy One of Israel”:

“Thus says the Lord, your Redeemer, the Holy One of Israel: “I am the Lord your God, who teaches you to profit, who leads you in the way you should go.” (Isaiah 48:17)

Thus, God is sent by God and the Spirit of God, which makes little sense unless read through the lens of the Trinity.

Verses That Teach That the Father is God, Jesus is God, and the Holy Spirit is God

Now that we’ve established that the doctrine of the Trinity is not restricted to the New Testament, we turn our attention to verses that state that the three persons of God’s being are equally God.

The Father as God: John 6:27 endorses the Father’s divine nature, where Jesus refers to God the Father as the one who sent Him and the one whom God the Father has set his seal upon.

Jesus as God: The divinity of Jesus is affirmed in several passages:

- John 20:28, where Thomas addresses Jesus as “My Lord and my God!”

- Mark 2:10, where Jesus demonstrates His divine authority to forgive sins.

- Romans 9:5, describing Christ as over all, God blessed forever.

- 2 Peter 1:1, referring to our God and Saviour Jesus Christ, further substantiating His Godly stature.

The Holy Spirit as God: The Holy Spirit’s divinity is evident in:

- Acts 5:3-5, where lying to the Holy Spirit is equated with lying to God.

- Matthew 12:32, discussing the unforgivable sin against the Holy Spirit.

- Hebrews 9:14, which speaks of the eternal Spirit.

- Romans 15:18-19 and John 14:26, highlighting the Spirit’s role in teaching and empowering believers.

Distinct Yet Unified

John 14:16-17 provides evidence that these persons are distinct yet united, as Jesus promises to ask the Father to send another advocate—the Spirit of truth. Finally, the baptismal formula proves that these three distinct persons are one being and, thus, share one name (Matthew 28:19). (See also Paul’s benediction in 2 Corinthians 13:14, where the three persons of the Trinity are placed on the same level).

Conclusion

These references are just a few of the many scriptural illustrations of the Trinity. Regrettably, we have not had time to consider the practical implications of the doctrine of the Trinity or the challenges with the Islamic view of God as a Monad. However, the article is becoming too long as it is. So, we will reserve those discussions for the subsequent article, if the Lord permits.

Notes

1. R. C. Sproul, “Everyone is A Theologian”, pg. 58